I first met Douglas White on July 31, 1992, on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. I didn’t know it at the time, but Douglas was soon to be indicted by Grand Jury. I only later learned that he had been accused of molesting his two grandsons and had already appeared in tribal court a year before. Douglas claimed to be innocent. A medical examination of the two boys found no physical evidence of sexual abuse. The U.S. Attorney’s office in Rapid City – which held jurisdiction on Major Crimes committed on Indian reservations – declined to prosecute. After a preliminary hearing, the case was dismissed due to “insufficient evidence.” A year later the case was picked up by the federal government and White was indicted on two counts of sexual abuse of a minor.

The process through which his (now federal) case was reopened remains unclear, but faced with either fighting the accusation or plea bargaining the charges down to a lesser sentence, Douglas pled innocent, received a court-appointed attorney, and chose to go to trial.

In an era when false memories of alleged sexual abuse resulted in numerous wrongful convictions (as in the McMartin case), an all non-Native jury, influenced by the government’s disturbing story, erred on the side of guilt. Despite the fact that White was an elderly man with no history of sexual abuse and that there was no evidence of sexual abuse actually committed in the case, that jury found him guilty on two counts of sexual abuse of a minor “beyond a reasonable doubt.” Douglas was sentenced to 292 months in prison without hope of parole.

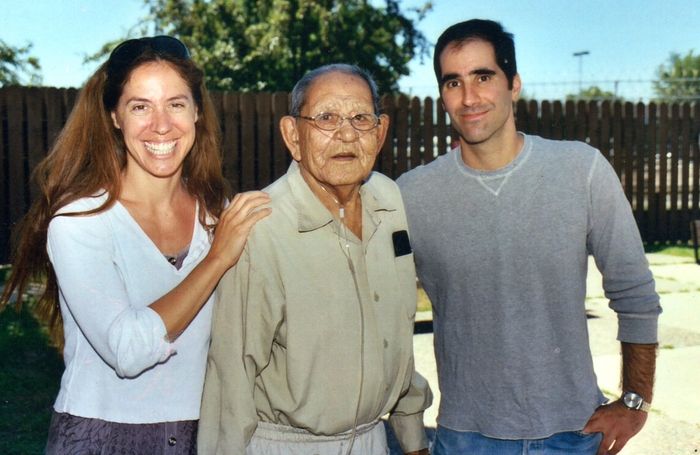

Jennifer and I began visiting Douglas in prison. We’d sit and talk for hours, buying him coffee, sandwiches, and desserts from the vending machines in the visiting room. He would tell us the most amazing stories illustrating them with hand gestures and body language and a mischievous sense of humor.

He was our friend. And he said he was innocent. He talked about his case all the time. He was always trying to figure out some way to get out, but each lead turned into a dead-end. I took a special interest in the details of his case. He sent us the 400-page transcript of his trial. It was disturbing to read the accusations against him. But the childrens’ testimony was even more disturbing because they answered “yes” and “no” to the same questions. Sometimes they wouldn’t even articulate their answers. They’d just shake their heads and that would have to be interpreted as a “yes” or a “no.” The case had no physical evidence – and contradictory testimony. I couldn’t understand how a jury convicted him.

For sixteen years, we regularly visited Douglas in prison. In 2006, Jennifer enrolled in a documentary film class at USC Film School. We agreed that Douglas would be an ideal subject, provided we could actually film him in prison.

That turned out to be an insurmountable hurdle. So we decided to shift the focus of our documentary project onto the court case itself. What we found was new evidence of his “actual innocence.”

Holy Man premiered at the Twenty-Seventh Annual Boston Film Festival in 2011. It won the Best Documentary and Best Director Awards at the Red Nation Film Festival (2012), and was a featured selection in DocuWeeks (2012), screening in New York City and Los Angeles.